Papua New Guinea - a million different journeys!

Papua New Guinea, in the southwestern Pacific, encompasses the eastern half of New Guinea and its offshore islands. A country of immense cultural and biological diversity, it’s known for its beaches and coral reefs. Inland are active volcanoes, granite Mt. Wilhelm, dense rainforest and hiking routes like the Kokoda Trail. There are also traditional tribal villages, many with their own languages.

History of Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA’S EARLY HISTORY

Our ancient inhabitants are believed to have arrived in Papua New Guinea about 50-60,000 years ago from Southeast Asia during an Ice Age period when the sea was lower and distances between islands was shorter. New Guinea (as it used to be known), one of the first landmasses after Africa and Eurasia to be populated by modern humans, had its first migration at about the same time as Australia, placing us alongside one of the oldest continuous cultures on the planet.

Agriculture was independently developed in the New Guinea highlands around 7,000 BC, making it one of the few areas of original plant domestication in the world. A major migration of Austronesia speaking peoples came to our coastal regions roughly 2,500 years ago, along with the introduction of pottery, pigs, and certain fishing techniques.

Some 300 years ago, the sweet potato entered New Guinea with its far higher crop yields, transforming traditional agriculture. It largely supplanted the previous staple, taro, and gave rise to a significant increase in population in the highlands.

In the past, headhunting and cannibalism occurred in many parts of what is now named Papua New Guinea. By the early 1950s, through administration and mission pressures, open cannibalism had almost entirely ceased.

A number of Portuguese and Spanish navigators sailing in the South Pacific in the early 16th century were probably the first Europeans to sight Papua New Guinea. Don Jorge de Meneses, a Portuguese explorer, is credited with the European discovery of the principal island of Papua New Guinea in around 1526-27. Although European navigators visited and explored the New Guinea islands for the next 170 years, we kept pretty much to ourselves until the late 19th century.

EARLY EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT OF PAPUA AND NEW GUINEA

New Guinea

The northern half of Papua New Guinea came into German hands in 1884 as German New Guinea. With Europe’s growing need for coconut oil, Godeffroy’s of Hamburg, the largest trading firm in the Pacific, began trading for copra in the New Guinea Islands. In 1884, Germany formally took possession of the northeast quarter of the island and put its administration in the hands of a chartered company. In 1899, the German imperial government assumed direct control of the territory, thereafter known as German New Guinea. In 1914, Australian troops occupied German New Guinea, and it remained under Australian military control until 1921.

The British Government, on behalf of the Commonwealth of Australia, assumed a mandate from the League of Nations for governing the Territory of New Guinea in 1920. That mandate was administered by the Australian Government until the Japanese invasion in December 1941 brought about its suspension. Following the surrender of the Japanese in 1945, civil administration of Papua as well as New Guinea was restored, and under the Papua New Guinea Provisional Administration Act, 1945-46, Papua and New Guinea were combined in an administrative union to become the country of Papua New Guinea.

Papua

On November 6, 1884, a British protectorate was proclaimed over the southern coast of New Guinea (the area called Papua) and its adjacent islands. The protectorate, called British New Guinea, was annexed outright on September 4, 1888. The possession was placed under the authority of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1902. Following the passage of the Papua Act of 1905, British New Guinea became the Territory of Papua, and formal Australian administration began in 1906. Papua was administered under the Papua Act until World War II, when Japanese forces invaded the northern parts of the islands in 1941 and began to advance on Port Moresby, suspending civil administration.

During the war, Papua was governed by a military administration from Port Moresby, where Gen. Douglas MacArthur occasionally made his headquarters. As noted, it was later joined in an administrative union with New Guinea during 1945-46 following the surrender of Japan, and Papua New Guinea was born.

FIRST CONTACT IN OUR HIGHLANDS REGION

Michael Leahy was an Australian prospector from rural Queensland who is known for making first contact with our highlands people in Papua New Guinea in 1932. Leahy and his brother Dan looked for gold and explored in the highlands for four years together with Patrol Officer James Taylor.

During his time here, Leahy documented his expedition in a daily journal and also captured an amazing series of photographs that were later discovered in 1983 by Australian writers and filmmakers Bob Connolly and Robyn Anderson. These two went on to make the award winning documentary, First Contact.

PAPUA NEW GUINEA, OCCUPATION AND WORLD WARS

During World War I, Papua New Guinea was occupied by Australia, which had begun administering British New Guinea, the southern part, as the re-named Papua in 1904. After World War I, Australia was given a mandate to administer the former German New Guinea by the League of Nations.

Papua, by contrast, was deemed to be an External Territory of the Australian Commonwealth, though as a matter of law it remained a British possession, an issue that had significance for the country’s post-Independence legal system after 1975. This difference in legal status meant that Papua and New Guinea had entirely separate administrations, both controlled by Australia.

The New Guinea campaign (1942-1945) was one of the major military campaigns of World War II. Approximately 216,000 Japanese, Australian and American soldiers, sailors and airmen died during the New Guinea Campaign. The two territories were combined into the Territory of Papua and New Guinea after World War II, which later was simply referred to as “Papua New Guinea”. The Administration of Papua became open to United Nations oversight.

PAPUA NEW GUINEA BECOMES A NATION

Elections in 1972 resulted in the formation of a ministry headed by Chief Minister Michael Somare, who pledged to lead the country to self-government and then to independence. Papua New Guinea became self-governing on 1 December 1973 and achieved independence on 16 September 1975. The country joined the United Nations (UN) on 10 October 1975 by way of Security Council Resolution 375 and General Assembly resolution 3368.

SINCE INDEPENDENCE

The 1977 national elections confirmed Michael Somare as Prime Minister at the head of a coalition led by the Pangu Party. However, his government lost a vote of confidence in 1980 and was replaced by a new cabinet headed by Sir Julius Chan as Prime Minister. The 1982 elections increased Pangu’s plurality, and parliament again chose Somare as Prime Minister. In November 1985, the Somare government lost another vote of no confidence, and the parliamentary majority elected Paias Wingti, at the head of a five-party coalition, as Prime Minister. A coalition, headed by Wingti, was victorious in very close elections in July 1987. In July 1988, a no-confidence vote toppled Wingti and brought to power Rabbie Namaliu, who a few weeks earlier had replaced Somare as leader of the Pangu Party.

Under legislation intended to enhance stability, new governments remain immune from no-confidence votes for the first 18 months of their incumbency.

The incumbent Prime Minister, Peter O’Neill, came into office in 2011.

THE BOUGAINVILLE CONFLICT

A nine-year secessionist revolt on the island of Bougainville claimed some 20,000 lives. The rebellion began in early 1989, over opposition to the world’s largest open-cut copper mine, Panguna mine. Active hostilities ended with a truce in October 1997 and a permanent ceasefire was signed in April 1998. A peace agreement between the Government and ex-combatants was signed in August 2001 on the condition that a referendum on Bougainville’s political status would be held within twenty years. A referendum is scheduled to be held in June 2019.

MUST SEE

Learn about Papua New Guinea’s independence history at the new exhibition at Independence House in Port Moresby.

Take a tour of the relics and memories of World War II history through Kokopo and Rabaul in East New Britain.

Gain permission to visit the archaeological sites at Kuk Valley, in Western Highlands, the first place on earth to cultivate land for gardening.

People of Papua New Guinea

Ethnic groups

Papua New Guinea’s social composition is extremely complex, although most people are classified as Melanesian. Very small minorities of Micronesian and Polynesian societies can be found on some of the outlying islands and atolls, and as in the eastern and northern Pacific these people have political structures headed by chiefs, a system seldom found among the Melanesian peoples of Papua New Guinea.

The non-Melanesian portion of the population, including expatriates and immigrants, is small. At independence in 1975 the expatriate community of about 50,000 was predominantly Australian, with perhaps 10,000 people of Chinese origin whose ancestors had arrived before World War I. By the early 21st century most of those people had moved to Australia. The foreign-born community had not expanded but had become more mixed, with only some 7,000 Australians; the largest non-Western groups were from China and the Philippines. The government sponsored the immigration of Filipinos in the 1970s to provide workers in skilled professions, and many entered business and intermarried locally. The unauthorized, illegal entry of other immigrants, notably from China, was an ongoing concern of the government in the early 21st century.

Languages

The official languages of the country all reflect its colonial history. English is the main language of government and commerce. In most everyday contexts the most widely spoken language is Tok Pisin (“Pidgin Language”; also called Melanesian Pidgin or Neo-Melanesian), a creole combining grammatical elements of indigenous languages, some German, and, increasingly, English. Hiri Motu is a simplified trading language originally used by the people who lived around what is now Port Moresby when it came under that name in 1884.

In addition to the official languages, there are more than 800 distinct indigenous languages belonging to two radically different language groups—Austronesian, to which the local languages classified as Melanesian belong, and non-Austronesian, or Papuan. There are some 200 related Austronesian languages. Austronesian speakers generally inhabit the coastal regions and offshore islands, including the Trobriands and Buka. Papuan speakers, who constitute the great majority of the population, live mainly in the interior. The approximately 550 non-Austronesian languages have small speech communities, the largest being the Engan, Melpa, and Kuman speakers in the Highlands, each with more than 100,000 speakers. Amid such a multiplicity of tongues, Tok Pisin serves as an effective lingua franca.

Religion

The majority of Papua New Guinea’s people are at least nominally Christian. More than two-fifths of the population is Protestant; Lutherans make up the largest portion of those, and there are some Anglicans and a growing number of Pentecostals. Approximately another one-fifth are Roman Catholics. Seventh-day Adventism is increasing in popularity, and there are also small numbers of Bahāʾīs and Muslims. Despite the apparent inroads made by introduced religions, much of the population also maintains traditional religious beliefs, and rituals of magic, spells, and sorcery are still widely practiced.

Cultural Life of Papua New Guinea

Cultural milieu and arts

Despite the penetration of the contemporary economy and media and the effects thereof on traditional cultural life, Papua New Guinea retains a rich variety of village cultures. These are expressed in the ways the country’s landscapes have been shaped over generations and in its people’s wood carving, storytelling, song, dance, and body decoration.

Carvings from the Sepik, Gulf, Massim, and Huon Peninsula regions are world famous. The best-known wood carvings come from the Sepik region, notably masks and crocodile figures that have religious connotations. Many sacred carvings from the giant men’s houses known as tambaran on the Sepik River have been sold and not replaced amid the decline of tourist traffic in the 21st century. In most areas only the older generations possess the skills for making traditional clay cooking pots, which are being replaced by metal pots and pans.

Across the country, wooden hourglass-shaped drums known as kundu remain essential for song and dance, especially during major national celebrations such as the anniversary of independence. Self-decoration, particularly for dance and rituals, remains important everywhere. Traditional musical expression is an essential indicator of local identity, and contemporary shows offer new opportunities for presentation to diverse audiences. The annual shows at Goroka and Mount Hagen involve thousands of dance group participants, and they attract many thousands of spectators from across the country and overseas.

In urban areas painting on canvas has become a vibrant cottage industry for local artists that is patronized by tourists, resident expatriates, and the local middle class. A wave of nationalist creative writing was produced during the transition to independence and continues despite occasional periods of diminished activity, but formal theatre declined in the decades after independence. Street theatre sponsored by aid donors is often used in awareness campaigns ranging from electoral training to HIV/AIDS education. The cities, especially, support a vibrant youth music culture; many local bands support a thriving commercial recording industry, and their songs are played on radio and television.

Daily life and social customs

People’s daily lives vary enormously in Papua New Guinea, with the great majority of the population living across the diverse rural landscape in villages or hamlets. Daily life usually centres on the extended family, whose primary responsibilities are producing food for subsistence and rearing children. Most people have rights to use portions of land for the growing of food and some cash crops as well as the rights to fish, hunt, and gather timber from local forests. Many of those activities are accompanied by rituals to ensure success and prosperity. Other major rituals, such as menarche ceremonies for girls and initiations for boys, are declining. The Highlands social system previously involved the strict separation of men and women, with men sleeping in men’s houses somewhat akin to military barracks and women sleeping in separate garden houses with the small children. With the incursion of newer cultural influences, that system has been modified in much of the region. Wealthy and prominent men with multiple wives retain separate households for each.

The clan forms the major unit of social organization. Almost all Melanesian societies are patrilineal, tracing descent through the male line, and even matrilineal societies, where descent is traced through the female line, remain patriarchal—i.e., male-dominated. In some areas descent and land rights can be claimed through either parent, so people can belong to both their parents’ clans. Marriage within a clan would be perceived as incest, and so marriage is only possible across clan lines and sometimes across the boundaries of a tribe. Large tribes are not the norm, but where they do exist they have a degree of political unity and can be viewed as federations of clans. They may share origin myths, and in such cases clans can be seen as being like “brothers,” sons of a founding father. These social structures form the lines of conflict expressed in the interclan warfare that persists in the Highland provinces, and in those areas they often form the lines of political competition in contemporary elections.

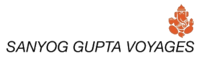

When people migrate from rural villages to urban areas or rural resettlement areas, they carry their languages and customs with them and re-create their existing social structures. Social bonds and obligations of the wantok system can provide support for those struggling in new locations but also create heavy demands on the more affluent people who feel obliged to support their kin. The demands of wantoks are often held to be a root cause of corruption. Increasingly there are second or third generations of townspeople who have “mixed marriages” across language lines, who while affiliated with both their parents’ relatives often display a greater sense of nationhood than their age-mates who have less multicultural backgrounds. Intergenerational tensions reflect the stresses of rapid social change in rural and urban contexts.

In both villages and cities, music and dance celebrations often mark important life-cycle events such as birth, death, initiation, menarche, economic transactions (even the opening of a roadway), peacemaking, and religious observances. Traditional expressions are now sometimes mixed with or even replaced by string band music, Christian hymns, or both, primarily reflecting modified influences from the West and from other Pacific Islands areas.

Cultural institutions

The Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery in Waigani, a suburb of Port Moresby, has a significant collection of ethnographic artifacts. The government’s National Cultural Commission, the Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies, and the National Film Institute record, document, and promote activities associated with traditional cultures, while organizations promoting tourism market aspects of those cultures to potential audiences overseas. In 2008 the Kuk Early Agricultural Site was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site. That land in the Western Highlands has been worked almost continuously for at least 7,000 years, and the site contains even earlier evidence of the beginning of organized agriculture and its subsequent development.

ReImagine Papua New Guinea

REIMAGINE THE DESTINATION YOU THOUGHT YOU KNEW

We asked people what they think about Papua New Guinea, and most believe it’s just remote tribes and coconut trees for days (cannibals also came up a lot too, we’ll admit it). We invite you to discover the unique experiences that most tourists have never imagined – including vivid festivals, delectable dishes, underground events, plantation tours, and hidden secrets found far off the beaten track.

Did you know that Ela Beach is the site of one of the world’s first beauty pageants? Or that you can scuba dive with migrating killer whales in West New Britain? When you go beyond the guided tours and venture past the landmarks you’ll realise there’s so much more to see, taste, and do in the land of a million different journeys. ReImagine Papua New Guinea today.